The subcontinent was effectively ruled by the administrative machinery of both the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire. The administrative system was based mostly on principles devised in Central Asia with Mughal rulers altering them according to the requirements of the subcontinent.

In this context, Mughal emperor Akbar designed an elaborate bureaucracy known as the Mansabdari system which ranked officers based on a number of troops they commanded. Though there was a clear distinction between the men of sword (Ahle-Shamsheer) and Ahl-e-Qalam (men of Pen) yet mansabdari system was a hybrid pattern whereby there was no distinction between military and civil assignments and both were

interchangeable. It was well-known that until the rule of East India Company that the payment of salaries to these administrative personnel varied from cash payments to in-kind payments such as land grants.

The East India Company was infused with the modern ideas of rule as well as administrative practices. The need for the civil service was felt soon after the Company acquired territories after the Battles of Plassey (1757) and Buxar (1764). The East India Company demanded and was given the right to collect

revenue known as Diwani through the Treaty of Allahabad that was signed in August 1765 between the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam.

Son of Emperor Alamgir II and Robert Clive in the aftermath of the Battle of Buxar in which a combined force of premier Muslim princes was humbled by a small force led by Major Hector Munro who later became command-in-chief of the Company armies.

The treaty of Allahabad was handwritten by Itisaam ud-din, a Bengali Muslim scribe who was a diplomat of the Mughal Empire.

The rights to collect revenue allowed the Company to collect revenue directly from the people of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. In return, the Company paid an annual tribute of twenty-six lakhs rupees, equal to 260,000 pounds sterling, while securing for Shah Alam II the districts of Kora and Allahabad.

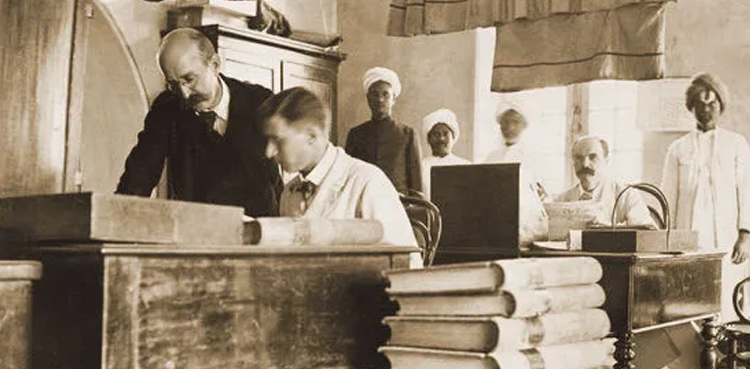

In the aftermath of revenue collection responsibilities Warren Hastings, the then Governor-General of Bengal created the post of District Collector who was made in-charge of collecting land revenue. This post was soon abolished on grounds of excessive concentration of powers and corruption. The British had systematised civil services by distinguishing it from the military services, creating a hierarchy of officials who were paid out of public revenues.

The consequences of massive corruption in the ranks of EIC civil service soon started creating negative consequences for the British politics as many civil servants became Nabobs (nawabs) and started manipulating parliamentary process through corrupting the rotten boroughs.

Attempts to regulate EIC activities began in the 1770s, with British Prime Minister Lord North (known to history as the chief executive who lost British American colonies) bringing in a Regulating Act 1773 followed by another act implemented by Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger known as Pitt’s India Act 1784 both of which sought to bring the company under closer parliamentary supervision.

Meanwhile a series of internal reforms under governor general Charles Cornwallisin the late 1780s and early 1790s saw the EIC’s administration radically restructured in order to eradicate private corruption. This was intended to improve both the lustre of its public image and the efficiency of its revenue-extracting machine.

After the acquittal of Hastings and the implementation of the Cornwallis reforms, the company attempted to rehabilitate its reputation.

Lord Cornwallis is usually known as the father of civil services in India and he was a peer of such sterling worth that his defeat in America did not affect his reputation for probity and a deep sense of duty. He introduced the Covenanted Civil Services and the Uncovenanted Civil Services.

The Covenanted Civil Services were created out of the law of the Company and it was the higher civil service comprising almost exclusively of Europeans who were paid very high salaries. The Uncovenanted Civil Services were the lower civil services and comprised mostly of native-born Indians and to some extent, Europeans too.

They were not paid as high as the Covenanted Civil Services.

Charter Act of 1833 provided that no Indian subject was to be barred from holding any office under the company.

This, however, did not alter the structure of British bureaucracy and it remained unaltered. Until 1853, the Court of Directors had the exclusive right to appoint persons in the Company’s civil services and these appointments were a source of privilege and patronage which the Company held on to very tightly. The Charter Act of 1853 provided for an open competitive examination for the recruitment of civil servants and deprived the Court of Directors of the power of appointments based on patronage.

This was recommended by a committee headed by Lord Macaulay. And consequently the first competitive examination was held in 1855.

After the Government of India Act of 1858, the higher civil service in India came to be known as the Indian Civil Services (ICS). The Indian Civil Services Act of 1861 provided that certain posts under the Government of India were to be reserved for persons who had been a resident of India for 7 years or more.

This paved the way for the entry of Indians into the higher civil services. The recruitment process involved examinations that were held in London and involved knowledge of subjects (Greek, Latin, English) alien to Indian natives and as a result, Indian representation in the services was negligible.

In 1860, the maximum age limit was lowered from 23 years to 22 years that was further lowered to 21 years in 1866. The Indian Civil Services Act of 1870 carried the process of Indianisation of civil services forward. Satyendranath Tagore was the first Indian to get selected in the Indian Civil Services.

Aitchison Committee was appointed by viceroy Lord Dufferin to recommend changes in the civil services. The Committee recommended that the Covenanted and Uncovenanted Civil Services should be changed

into Imperial, Provincial, and Subordinate civil services.

ICS came to be regarded as the steel frame of the British rule in India and it provided the support for maintaining control over the vast territories of the British Empire.

With the August Declaration of 1917 by Edwin Montague in the House of Commons, which had promised an increase in the association of Indians in the administration, the proportion of Indians in the civil services began to increase significantly and by 1930s Indians were in majority in the civil services.

A further prod to the inclusion of Indians in the service happened in 1912 when the Islington Commission suggested that 25 % of the higher posts be filled by Indians.

It also recommended that recruitment to higher posts should be done partly in India and partly in England and from 1922 the ICS exam was held in India. Viscount Lee Commission, set up in 1923,

had recommended the creation of a public service commission for the purpose of conducting examinations to recruit the civil servants. Accordingly, a public service commission was set up in 1926 under the chairmanship of Sir Ross Barker.

All India Services were designated as Central Superior Services in 1924.

After 1939, the number of Indians in the service increased because of non-availability of Europeans. The Government of India Act, 1935 enlarged the powers of the commission and made it a Federal Public Service Commission.

By 1934, there were seven All India Services including the Indian Forest Service, Indian Police, and Indian Political Service.

Lord Cornwallis is usually known as the father of civil services in India and he was a peer of such sterling worth that his defeat in America did not affect his reputation for probity and a deep sense of duty. He introduced the Covenanted Civil Services and the Uncovenanted Civil Services. The Covenanted Civil Services were created out of the law of the Company and it was the higher civil service comprising almost exclusively of Europeans who were paid very high salaries.

The Uncovenanted Civil Services were the lower civil services and comprised mostly of native-born Indians and to some extent, Europeans too.

They were not paid as high as the Covenanted Civil Services.

Charter Act of 1833 provided that no Indian subject was to be barred from holding any

office under the company.

This, however, did not alter the structure of British bureaucracy and it remained unaltered. Until 1853, the Court of Directors had the exclusive right to appoint persons in the Company’s civil services and these appointments were a source of privilege and patronage which the Company held on to very tightly. The Charter Act of 1853 provided for an open competitive examination for the recruitment of civil servants and deprived the Court of Directors of the power of appointments based on patronage.

This was recommended by a committee headed by Lord Macaulay. And consequently the first competitive examination was held in 1855.

After the Government of India Act of 1858, the higher civil service in India came to be known as the Indian Civil Services (ICS). The Indian Civil Services Act of 1861 provided that certain posts under the Government of India were to be reserved for persons who had been a resident of India for 7 years or

more. This paved the way for the entry of Indians into the higher civil services. The recruitment process involved examinations that were held in London and involved knowledge of subjects (Greek, Latin, English) alien to Indian natives and as a result, Indian representation in the services was negligible.

In 1860, the maximum age limit was lowered from 23 years to 22 years that was further lowered to

21 years in 1866. The Indian Civil Services Act of 1870 carried the process of Indianisation of civil services forward. Satyendranath Tagore was the first Indian to get selected in the Indian Civil Services.

Aitchison Committee was appointed by viceroy Lord Dufferin to recommend changes in the civil services. The Committee recommended that the Covenanted and Uncovenanted Civil Services should be changed

into Imperial, Provincial, and Subordinate civil services.

ICS came to be regarded as the steel frame of the British rule in India and it provided the support for maintaining control over the vast territories of the British Empire.

With the August Declaration of 1917 by Edwin Montague in the House of Commons, which had promised an increase in the association of Indians in the administration, the proportion of Indians in the civil services began to increase significantly and by 1930s Indians were in majority in the civil services.

A further prod to the inclusion of Indians in the service happened in 1912 when the Islington Commission suggested that 25 % of the higher posts be filled by Indians.

It also recommended that recruitment to higher posts should be done partly in India and partly in England and from 1922 the ICS exam was held in India. Viscount Lee Commission, set up in 1923, had recommended the creation of a public service commission for the purpose of conducting examinations to recruit the civil servants. Accordingly, a public service commission was set up in 1926 under the chairmanship of Sir Ross Barker.

All India Services were designated as Central Superior Services in 1924.

After 1939, the number of Indians in the service increased because of non-availability of Europeans. The Government of India Act, 1935 enlarged the powers of the commission and made it a Federal Public Service Commission.

By 1934, there were seven All India Services including the Indian Forest Service, Indian Police, and Indian Political Service.

Evolution of civil service during British rule

Leave a Comment