Turning to a bowl on her drawing room table, Amra Javed picks up the desiccated shrubs that by now had become ornaments, and passionately tells their back-story: “I collected these from under the sesame plant and some trees and look! They are still so aesthetically pleasing!”

When asked of the Bus Rapid Transit system of Karachi, the social worker expressed gloom and recalled the 9,000 trees that became the casualty of the last BRT line — Green Line– that was developed on one of the five routes charted out over 15 years ago under Karachi Breeze project.

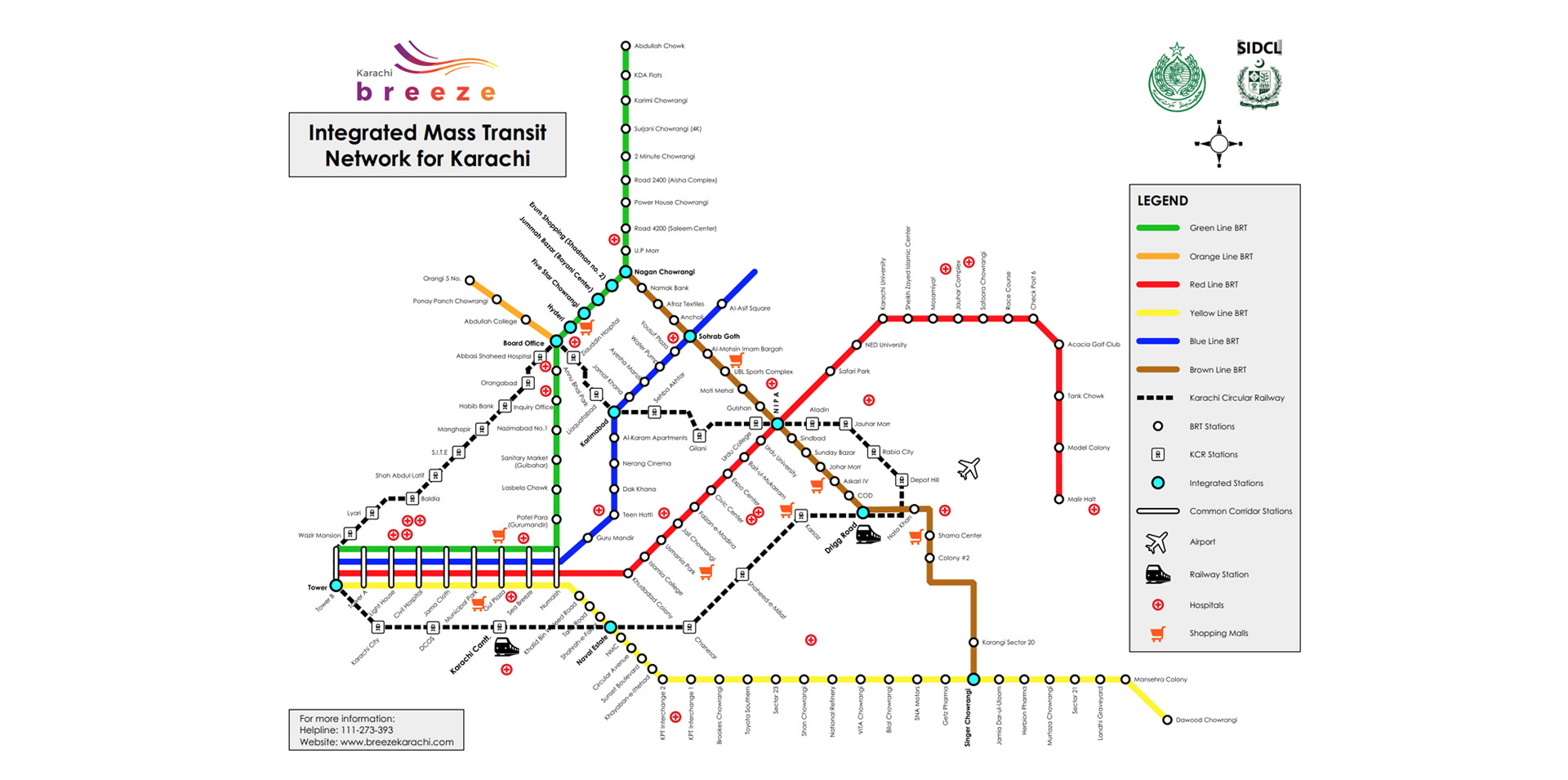

In 2008, a Japanese company JICA identified routes for an integrated mass transit system for Pakistan’s cosmopolitan with roughly 30 million people in it. The project was by the Sindh government and was to kick-start shortly after its assessments.

It is to have five bus lines for five routes in the transport-poor Karachi, and a circular railway, accompanied with bike routes, which together would solve Karachiites’ woes and save them a heavy budget on privately managing transports and the time that goes in commuting in absence of public transport. However, despite passage of a decade-and-a-half, the project is still less than half-done.

The damages this has caused are numerous, including financial, infrastructural, and on people’s collective physical and mental health, but let’s have a look at how it risks Karachi’s already volatile climate.

“It is depressing to even talk about rehabilitating the city landscape now after so many heartbreaks on part of ill-conceived state policies and lukewarm efforts,” Javed lamented.

Ready to express her incensed critique, Javed is not out of place. She has seen terribly failing many a bid of transplantation of full-grown trees that become the costs of development in the cosmopolitan.

ALSO READ: Bengalis in Pakistan forsake culture, language for chance at citizenship

ALSO READ: Dams or no dams? Indus Delta people have something to say

ALSO READ: What you should know about survivors of floods 2022?

“Before we resisted the state apathy towards climate, you could see the ruthless uprooting and killing of these trees without any remorse,” Javed said, adding that things have changed at least to a point that projects now conceive a plan to transplant these trees or plant saplings as consolation to chopping the trees down.

But then why the dejection if things are improving? Javed explains that in her four decades of environmental activism, barely any transplantation plan has seen the light of the day.

Last she checked the city authorities didn’t even have the tree excavators for safe digging of roots, so that these can be then transplanted elsewhere. The rate of the transplantation bids succeeding is almost zero, she claims.

Looking back at one similar instance, in the first developed BRT, Green Line, the cost borne by Karachi’s already declining vegetation index was well over 7,000 trees, according to government’s own records. While onlookers differ and contradict the numbers, citing a much bigger number, if we go by the official numbers of tree casualty, only four trees were transplanted to “outdo” the climate impact.

In its assessment, the horticulturists outsourced to salvage the environmental impact said they would transplant 800 trees only, because rest of the chopped trees were Conocarpus, harmful for the Karachi environment.

ALSO READ: HIV disinformation: ‘patients fear resentment over death in Pakistan’

ALSO READ: Karachi woman’s love for football inspires her entire community

In later phase, they only attempted to replant 12 trees, and since the timing and atmosphere were not taken into account while doing this exercise, only four of them survived. “Those four trees, are like stuff you tuck away that nobody uses now,” said Javed on the benefit of the transplantation.

The Red Line will span 26 km from Safoora Goth to Numaish, where it would converge in the Green Line to finally reach [Merewether] Tower. It is expected to have an average daily ridership of 625,000 passengers.

But on its way, experts say it will run through the mortuary of about 50,000 trees. On the other hand, the official assessments say there are over 23,000 trees out of which little over 9,000 have to be uprooted.

Out of the uprooted trees, little more than 12,000 are Conocarpus which wont be transplanted, but “the rest will be”, confirmed Pir Sajjad Sarhandi, Manager Planning & Infrastructure for Trans Karachi, company overseeing Karachi Breeze project.

This has indeed been our predicament that we never work in coordination, and right after the completion of one development project, we would dig that up to then lay “utility lines causing damages to exchequer and infrastructure”, admitted Sarhandi. He added that the same has happened over and over again with mitigating environmental impacts and replanting trees that were chopped for some projects.

However, the manager assures this time around things would be different. “We will make sure the transplantation takes place and we will factor in the weather and the right equipment required for safest attempts.”

He said their contract with Asian Development Bank requires them to lessen the environmental cost as much as possible.

“For each tree uprooted, we have vowed to plant five trees,” he said.

While for the longest time the government people and their outsourced horticulturists have promised rehabilitation of the greenery flattened to pave way for development, it has rarely, if ever, come to pass as Javed has said.

Environmentalist and a horticulture park owner Tofiq Pasha says it’s “a financially lucrative arrangement” to plant ill-suited trees on green belts, for which the officials secure heavy budgets.

“These trees either don’t grow and you have to secure another budget for another round of plantation, or you cut them down citing their inaptness for the local climate and then uproot them to secure another budget.”

Javed and Pasha both lament the apathy and naivety of officials towards environment and what’s appropriate for the cosmopolitan beset with climate change and heat.

“They know when and where a project will be constructed, they still plant trees there and let them grow and develop their roots between the project approval and its inauguration,” Pasha dreads. He said that the officials always know it’s not going to last and that its a waste of money and damage to environment.

They either do it to look good to people that they care about environment and city’s greenery, or they manage to make good money off the top in contracts.

To understand why the green spaces and its decline a grave and sensitive topic, urban planner and mapping expert Muhammad Toheed said his study and analysis of NDVI suggests 40 of green space reduction in Karachi in the past 20 years till 2021.

“If I carry out an NDVI now, it will most likely show a drastic further decline, after Green Line and Red Line, among other sprawling developments.”

Soha Macktoom, an architect and associate director at KUL, dresses down the hollow promises and trends used to attract attention but for the most part bear little to no fruit.

“Now a days everybody wants to set up urban forests, it’s the new catchphrase,” Macktoom says, adding that while it’s important to have that certain typology in the specifically carved out spaces in the cities, it’s however not all the Karachi needs.

“If you want to find a shade in an increasingly hot Karachi in the middle of a busy outdoors day, would you go all the way to those distant urban forests?”

We are likely to have increased instances of heat waves in coming years, as result of the heat island effect in Karachi, and for relief of people, we need more trees within the city whose shade is afforded to anyone and everyone, she said.

But with trees cut down so ruthlessly, and casualties of thousands of people in heatwaves failing to warrant radical actions and strategies in ever-expanding Karachi, one can’t help but question the livability of this city in years to come.

Leave a Comment